The writer Caroline Ross is the author of two novels, The War Before Mine and Small Scale Tour, both published by Honno. Overners, her third novel, for which she received a second bursary from Literature Wales, is now at the final draft stage.

Caroline was brought up on the Isle of Wight, experiencing a rural childhood that she drew on in The War Before Mine and which is revisited in much more detail in Overners, where she links the island’s rich archaeology to lives of women and girls in the period 1950 to 1970, a time of great change.

In her twenties, Caroline spent seven years in Newcastle upon Tyne. As the partner of Teddy Kiendl, artistic director of Live Theatre Co at the time, she developed the understanding of theatre that informs Small Scale Tour. The couple then lived in London, where Caroline worked as a journalist and editor for various publications, including The Illustrated London News, Punch, The Economist, The Observer and Euromoney. In the nineties, the couple moved to Wales to bring up their two sons, Alex and Cash.

As well as novels, Caroline has had short stories published and broadcast. She has taught creative writing to degree level and conducted many writing workshops. She is always interested in hearing from readers (see contact details). Caroline enjoys cross-country running and cooking chocolate brownies! Her fail-safe recipe can also be found on this site. (Recipe)

News

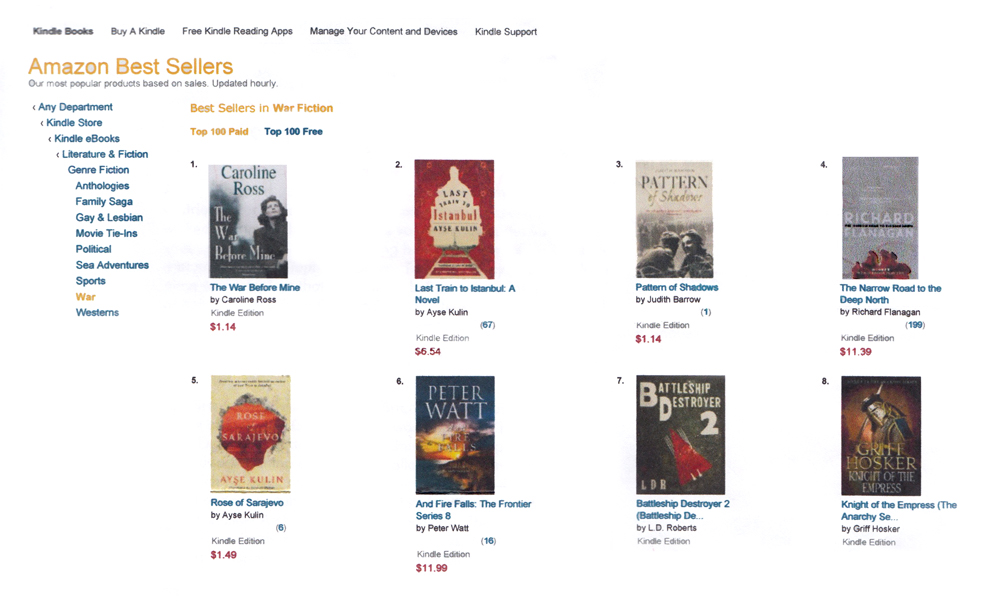

The War Before Mine has been available on Amazon Kindle since 2013 and has been selling well, both in the UK and abroad.

In June it reached the top spot in two categories in Australia: number one in War and number one in Historical Romance.

The Jungle Squaw

Once, long ago, Cheng’s father told her, their people had wandered a vast forest, free of all foes save snakes and tigers. They’d hunted and gathered, cutting down trees only here and there to plant and harvest rice before moving on through a land that teemed with souls. Then, out of the north, came pale enemies. They were soulless farmers and hungry; they wanted the best land and they fought Cheng’s people for it, clearing the lowlands of trees. Gradually, the first people were pushed into the mountains. Even there they were pursued, but by becoming watchful and very brave in combat, they survived.

Centuries later, led by greed and desire for dominion, the French came. Their rule of the land little affected the first people in their steep-sided forests, but later, when war broke out, French soldiers hacked through the trees to the village, seeking help. In return for brave fighters, the French offered arms and promised the first people their own domain, guaranteed forever. Bloody fighting followed. The country divided into two. Defeated, the French withdrew, taking with them the first people’s hopes, but leaving them their enemies, now both to the north and to the south.

Now, hardly anyone could remember a time of peace, and as things grew worse, Cheng longed for the return of their French friends. Instead of that, and at a critical moment because the village was surrounded, came three Americans with many bullets. The village was saved. They celebrated with rice wine around the fire.

The young sergeant had learned a little French at high school. Enjoying himself for the first time in many months, he laughed and joked with the village chief. The chief wanted to show his gratitude. He offered Cheng, his daughter, to the sergeant. The sergeant smiled and shook his head, but the old chief insisted, and that night after drinking much rice wine the sergeant and Cheng lay together in the cool and comfortable raised house. Afterwards, he stared up through the circular hole in the roof at the stars, so much brighter than he’d ever seen them, and then looked shyly across at Cheng, whose alert eyes shone too. He felt strangely at home.

They spoke to each other in broken French. He called her Cheng or sometimes in the raised hut at night ‘my amour’. She called him ‘Sergeant’. They were young, strong, and though living in an intense war, innocent. When he went away fighting with young men from the village, she thought achingly of him as she pounded rice on the stone, comforted by his parting promise to return.

He did come back. Many times. The Americans saw the advantage of an alliance with such good fighters, totally reliable in all situations save one. For as the sergeant laughingly reported to his commanding officer when back at base, ‘If they see a wild pig, they go apeshit. I mean go really crazy! Abandon everything in pursuit of the pig.’

Sometimes, the sergeant went away for longer periods but he always returned, bringing Cheng gifts: delicious coloured sweets called Chuckles, a puzzling thing called a bra, and little white pills, one of which he explained she must take every day. He gave her a gun called a Carbine and showed her how to use it.

One wet evening he came back to find the village in despair, for though a hunter had carried in a large pig earlier that day, no one could light the fire. From out of his pocket the sergeant produced a little piece of what looked like white clay. He placed it among the sticks and struck a match. The moment his match ignited the magic clay and the wet wood burst into flame was the moment the sergeant became beloved of all. Years later he remembered that night, seeing again the people around the fire laughing and licking their fingers, their cheeks glistening with pork fat.

Cheng felt the honour of being the sergeant’s wife. She started to call him ‘Mon Lieutenant’, so he would feel this appreciation. She made him a beautiful basket, light comfortable and strong, that he could carry on his back. The next time he had to go away fighting she watched him pack the basket, starting at the bottom with the grenades.

On his return he disappointed her by bringing only a piglet. She frowned. ‘Beaucoup p’tit,’ she said, but he told her to weave it a pen and let children play with it. Soon, he came back with another small piglet. ‘Une fille,’ he said, ‘une fille,’ giving her to understand that this way, they could eat pork much more often.

Was it because their days were filled with perils that their nights became so passionate? The village had to fend off regular attacks; the sergeant’s orders led him into fierce firefights in the jungle. In the raised hut their miraculously undamaged bodies demanded, and then demanded more. It was like being a guitar string pulled over a fret, the sergeant thought, you needed to be played and played. Exhausted but not sated they gazed up at the stars, perplexed at this limitless hunger.

Around the time the sow gave birth to a large litter the sergeant told Cheng he was leaving, not for a few days with the village fighters but for ‘toujours’. Another American would come to help her people, he said. She looked at his troubled face. That night in the raised hut he whispered the phrase he’d practised, ‘Je te remercie, ma belle femme,’ though he wasn’t sure whether she understood him or not.

On the long, long plane journey to San Francisco, he caught the eye of the stewardess. She liked these Special Forces guys, this one clearly fresh from the jungle and wearing all kinds of tribal jewellery. ‘Man, he was just so…exotic,’ she told a friend afterwards, giggling. ‘Okay so what if I made the first move? It’s 1967! Things change!’

While the other passengers slept they screwed behind the curtain at the back of the plane, among the dirty meal trays. The perfume of her hot skin bothered him, made him think of Cheng’s scent of earth and smoke, of the raised hut open at the top to the stars.

The years rolled. The sergeant left the army, established a career and got married. In Cheng’s village another American arrived and left, and then another, and then all the Americans went home. Their war had ended, but for Cheng’s people it continued. Several young men, including Cheng’s second husband, were killed over the next few years. Cheng used her carbine many times to save herself and her three children.

Much reduced, they were forced to retreat deeper and deeper into the forest, obliged to settle in bad places where snakes and other poisons abounded. The snakes killed their pigs. The old people died of hunger. Though a tiger had not been seen by anyone for three winters, a tiger took Cheng’s youngest son.

Anxious and filled with guilt about the fate of the first people, the sergeant could find out nothing until years later, when he read of their plight in a newspaper report. He and others like him gave money to help rescue the small number of survivors and bring them to America.

‘Are you out of your fuckin’ mind, giving away all that money?’ his second wife yelled when she saw the bank statement. ‘What were you thinkin? What about our kids for chrissake?’ He couldn’t explain in words she’d understand. He’d only once mentioned Cheng and she hadn’t understood then. Saying nothing, he opened the door of the icebox. ‘Is this some shit to do with your jungle squaw?’ The sergeant stared emptily into the icebox’s engorged interior. A pale slab of pork seeped watery blood onto a white plate. He felt sure Cheng and all the people he’d loved were long dead.

‘I did it in memory of my youth,’ he murmured more-or-less to himself, snapping open a can of Coke and stepping outside into the petrol-scented night. When a car backfired he leapt sideways, spilling Coke on his shirt.

The first thing Cheng bought in America was a packet of Chuckles to share with her son and daughter. She rolled the coloured sweets onto the plastic tabletop and they ate them looking out over rows of cars in a parking lot. Cheng found life in America strange, though her children adapted. Sometimes, she’d drive out of the suburbs to walk in the woods, removing her shoes so as to feel the forest floor under her feet and touching the bark with her hands to sense the trees’ unquiet souls.

Many years passed. One day, across a line of supermarket checkouts she thought she saw her Lieutenant. He’d become fat, had lost much of his silky dark hair, but his eyes had that same look of alertness, as though ready for the enemy to open fire from behind the tins of soup.

He noticed the clever hands first, deftly packing groceries into a paper bag. Looking upwards he saw they belonged to a broad faced, broad-hipped woman of about 60. She could be Mexican, or perhaps… Their eyes met, two forest deer glimpsing each other across a clearing.

‘Come on!’ his wife said. ‘We’ll be late for the graduation!’ And then in the car several minutes later, ‘Shit! What’s gotten into you? You just ran the red light!’

This is not a tale with a happy ending; survival is all the happiness it offers. Cheng and her Lieutenant still dream of the forest, and in their dreams and memories it will always be there. But their enemies have eaten the trees. They have found a use for the mountain slopes and planted there, in row upon orderly row. Each summer, wearing broad, conical hats to keep the sun from browning their skins, people harvest the crop. One pauses for a moment on the spot where the raised hut once stood. She straightens her back, sets down her basket of blood-red berries. All around, as far as her eyes can see, the rows of coffee plants stretch far away.

ENDS

Novels

"Moving and involving. As it shifts from delicate love story to scenes of gunfire

and battle, the pace never relents, its characters both appeal and convince."

James Friel.

The War Before Mine

2006 and Alex Mullen is coming to terms with a terrible past. Meeting up with Frankie, who shared the bad times, exposes one of Australia's cruellest secrets. Falmouth, 1942 and commando Philip Seymour sails for France. Left on the quayside is Rosie, a half-Romany girl looking for something more from life than collecting old clothes to sell on for pennies. Philip, who turned down a commission on principle, his pal Tucker, haunted by dreams of strange beasts hanging in his father's cold store, and Anderson, a mean spirited wide boy who Philip doesn't quite trust, are about to make history in the audacious raid on the docks of St Nazaire.

What befalls the commandos shapes the lives of Rosie, Alex and Philip in ways none of them could have imagined...

World War II: The raid on St Nazaire

Caroline’s meeting with survivors of the 1942 commando raid on St Nazaire, one of the most daring of World War II, inspired the novel. A British destroyer, the Campbeltown, was disguised as a German vessel, sailed up the estuary of the River Loire and rammed at full speed into the dock gates. The boat and its accompanying flotilla of launches came under heavy fire, but were successful in putting the dry-dock facilities, essential to German naval ambitions, out of action. Five VCs were won on the raid, the largest number ever awarded for a single action.

From The Sunday Telegraph Magazine: 14th December, 2008

by Melissa Katsoulis

Praises are already being sung for 'The War Before Mine', a debut by the journalist Caroline Ross. An impeccably researched saga of the far-reaching effects of Second World War at home and abroad, it follows a half-Romany girl called Rosie who is left behind, pregnant, when the love of her life goes off to fight.

From Historical Novel Review Nov 2011

The War Before Mine, Caroline Ross, Honno, 2011, £6.99, pb, 410pp, 9781870206976

A hugely enjoyable read, easy yet well-informed, light yet crammed with poetic images and unafraid to confront the harshness of war and its long-lasting consequences.

Sara Bower.

Small Scale Tour

Caroline's latest novel is Small Scale Tour

To see Caroline reading her first chapter click here and login as 'guest'

Click here to read Caroline's article in the winter edition of The New Welsh Review

Ham is resting – if that’s what you can call 12-hour shifts in Najib Khan’s corner shop. The acting work has dried up, but the shelf stacking and ‘wagging of chins’ with his eccentric Afghan employer is proving fertile ground for his latest project. Prompted by a desire to make his fortune at last, Ham turns to scriptwriting and finds himself confronting the time, 30 years ago, when it all went wrong.

Love, lust, jealousy and death – all in Kicking Theatre's bloodiest production.

So it’s very different from The War Before Mine, but hopefully you’ll find the characters just as engaging and there’s history in it too, Shakespeare’s company, and the origins of theatre in Greece…

“Grave comedy, tender tragedy and modern history play all in one, the scope of this fine book is anything but small. Her characters might dream of London, but her sharp-edged focus on their time and place lights up a whole era.

Mixing first-hand experience with a wise unsentimental humour, not to mention some dazzling writerly tricks, Small Scale Tour is a tremendous performance.”

Philip Gross

A taster:

Chapter 1 – you could say it is a novel that starts at the end…

Epilogue

It was January. Thirty years is too long ago to remember the exact dates, though I can still recall the exact intensity of the cold. Cold as only northeast England on a direct trans-Siberian windway could be. Cold like it used to be cold; the earth rock hard for months; trains going north from London iced up on the inside before they hit Doncaster; a cloud of dragon breath fogging the view every time you opened your mouth.

Perhaps travelling there in the truck made it feel like a show. One final gig on the tour. A get in, a performance and a get out, which is what theatre people call packing up the set after the play. Cuff’s get out, to be precise. His last, because there was no getting back in once you were nailed down under half a ton of frozen earth.

The truck groaned out of the city, past the Vickers tank factory and along bombed-out Scotswood Road, the newish Cushy Butterfield pub a big red sore amid amputated terraces and wasteland. Skinny kids trying to play football on the rough ground hugged themselves and moved in slow motion. Stafford drove, with Greg and me crammed in the cab beside him.

It was the second funeral we’d been to in four weeks, which perhaps explained why nobody felt like saying anything. I thought about that other, empty ceremony as the city slowly petered out, the truck starting to climb through brown villages interspersed with scrubby woodland.

Greg and Stafford chain-smoked with the windows half down. Finally, I complained, ‘Fuckin’ Arctic in here,’ after which they silently finished their tabs and wound the windows up.

Outside, the landscape turned into Northumbrian tundra, the tarmac disappearing under the wheels of the truck paled to ashen, nothing but a spatter of crows in the sky. Up here, the wind blew so hard it stunted and contorted the trees into bent, spiked things that looked like Martha Graham dancers in something alienating. No, actually, that’s as I want to see them now, conscious of employing a sophisticated image that will mark me as knowing something about art. Back then, none of us – with the exception perhaps of Greg – knew or cared who Martha Graham was.

‘You going to make a speech or anything?’

I asked, just to break the silence. Greg shook his head.

‘Sam’s reading.’

He paused before adding,

‘Alice and Maureen are doing something.’

Stafford rolled an eye towards him.

‘They never are!’

‘A duologue,’ said Greg, glumly.

There was silence again for a bit while we all pictured Alice and Maureen doing their duologue.

I remember watching them in Cuff’s garden, working on the play – that play – and I see Cuff frowning, stroking the soil from a bunch of carrots, nodding his frizz of grey hair as Greg declaims, pacing the veg patch, restless and dangerous-looking, banging his forehead with the heel of his hand to summon up ideas, ‘C’mon. C’mon…’

How Greg ever found his way to directing a theatre company in Newcastle Upon Tyne I’ll never know, because he’d been brought up in South America, his mother some Peruvian aristocrat, his father American. He was about thirty when Cuff died, but seemed younger. Black hair, short black beard, he looked like someone who’d swung in across the Atlantic on the end of a rope, Errol Flynn style, and true to the type, he’d actually served as a soldier in Vietnam. One time, walking with him down the Bigg Market, a car backfired. He dived for cover in to the gutter, entertaining a passing group of lasses no end.

Meeting Greg was a bit like waking up and finding a hoopoe in your garden. It looked so vivid and exotic a bird you thought it couldn’t possibly belong, but, strangely, it did. His productions were good. That outsider’s eye for the truth of the thing. Think of Altman doing Gosford Park, or Ang Lee doing Ice Storm. So it was with Greg directing plays about working class northerners, which was Kicking Theatre’s brief, back then.

Read more at Amazon

Caroline is now in the final stages of editing Overners, and gratefully acknowledges the help she received from Literature Wales in the form of a writer’s bursary which allowed her valuable time off work to develop the novel.

The action of Overners takes place largely on the Isle of Wight, where a plane filled with honeymoon couples crashes in 1957. The impact of this is felt by those who live in the rural hamlet nearest the site of the accident, a location also rich in archaeological remains and filled with ancient secrets. In 1970, this sleepy rural area also becomes the site of the famous Isle of Wight Pop Festival, attended by 600,000 people from all over the world

As in ‘The War Before Mine’ the novel has been partly inspired by true events. A flying boat crashed into the hill behind the house where Caroline was brought up in 1957. Thirteen years later the pop festival was held just a mile away, an event remembered now for its huge audience, its rollcall of rock stars, and the last ever performance of Jimi Hendrix, which took place on the final day.

Click here to read Caroline's article in the winter edition of The New Welsh Review

The following article by Caroline Ross appeared in The Western Mail in December 2008

to mark the publication of The War Before Mine.

It’s very good advice to write about what you know, so what on earth did I think I was doing writing The War Before Mine? When the Thought Police call round, I’ll just have to come clean. It just happened, Officer, honest, I’ve no idea what came over me. Suddenly started writing about a commando in the second world war, a part-Romany girl and a kid that gets taken to Australia. None of which I have any experience of… oh and then there’s that bit about the dog…

But that’s the most interesting thing about writing: it takes you to places and times you would never otherwise see, takes you inside people you’ve never met. Along with my commando, Philip, I found myself back in 1942 saying goodbye to a lovely girl and sailing off to do my duty in the daring Raid on St Nazaire, very uncomfortably aware I might never be coming back, and very afraid of what was to come.

Then, my hand in Rosie’s (the lovely girl’s) I joined the ATS, snapped on stockings coarse enough to sandpaper planks and, in between thinking about Philip and making new friends, learned how to tell a Jonkers 87 from a Messerschmitt. Still later, I followed my child character, Alex, as on unsteady four-year-old legs he ran about the deck of the SS Asturias as it sailed out of Southampton, completely unaware of the fate that awaited him in Western Australia.

Oh dear. The police officer’s back. And I forgot to tell you. She’s a woman. ‘Why are you writing about male aggression when there are so many interesting women’s stories out there?’

‘Rosie’s a woman,’ I say. ‘Her story’s just as important as Philip’s.’

‘Yes. But you should have stuck to Rosie. You didn’t need to follow Philip in the war. Is there something weird about you wanting to write about men?’

It’s the old question. Can men write good women and can women write good men – and bad men come to that, and handsome, sexy young men? Calm down, Caroline. You’re a bit

old for this. Concentrate. Of course women can write about men, in war or not. Pat Barker, for one, does that very well. And the thing is Officer, I didn’t intend to write this novel. I was pushed.

It’s true. You do get pushed. You meet people and see things that nudge you in unexpected directions. I met a wonderful man called Billie Stephens who was captured in the raid and later broke out of Colditz. I met Micky Burn, a commando on one of the launches that followed the destroyer Campbeltown straight into the German guns lining the estuary of the Loire. Micky turned out to live under an hour away from me in Penrhyndaedraeth. He told me his memories, and showed me letters men under his command had written to him on the eve of departure, including one from a soldier who clearly foresaw his own death in the raid.

In writing men in war it also helped to be married to a Vietnam vet. who knows what it’s like to feel five minutes away from certain death. My husband had to put up with a lot of questions.

But men fighting?

Women fought too. I talked to my mother. I talked to her friends, and in the diaries and letters now kept in the Imperial War Museum, I met many other women who’d joined up. They wanted to win the war, you know. Take Francoise, my French Resistance girl. I’m sure she’d say bollocks to the idea of fighting as an outlet for male savagery quite unknown to us

nice girls…

‘I think you’d better watch your language.’

It isn’t gung ho GI Joe stuff. Battles can be about love as much as war – love for those you leave behind of course but, above all, love for your comrades, the men and women in whom you put your trust.

‘Just what exactly are you after, writing this?’

Not fame and fortune, though that might be nice. No Officer – you know what I want? I want it to seem truthful. The most pleasing reaction to the book I’ve had so far was from Micky Burn, who told me the characters and the way they behaved towards each other felt right. Except perhaps the bit about the dog…

‘Ah yes. I was coming to that. Do you realise that you are in contravention of statute six, article nine of the Cruelty to Animals Act?’

‘I can assure you, Officer, no animal was killed, injured or otherwise harmed in the making of this book. It may feel like it... Actually as a writer I rather hope it does…

‘I think you had better accompany me down to the station.’

Review from The Sunday Telegraph Magazine: 14th December, 2008

by Melissa Katsoulis

Honno,the Welsh women's publishing co-operative which has just celebrated its 21st birthday, has been gaining increasing respect for the excellent books it brings out. Praises are already being sung for 'The War Before Mine', a debut by the journalist Caroline Ross. An impeccably researched saga of the far-reaching effects of Second World War at home and abroad, it follows a half-Romany girl called Rosie who is left behind, pregnant, when the love of her life goes off to fight.

What happens to her, the men destined for a crucial mission at St Nazaire and the young life caught up in the shameful, enforced depatriation of children to Australia, echoes down the generations and is never fully resolved.

Effortlessly skipping from the present day to 1942 and between the bedroom and the battlefield, Ross proves herself a versatile and sensitive chronicle of the world at war and a bright new star of Welsh writing.

From Historical Novel Review Nov 2011

The War Before Mine, Caroline Ross, Honno, 2011, £6.99, pb, 410pp, 9781870206976

On the face of it, Caroline Ross’s debut tells an oft-told story. Soldier on the eve of action has whirlwind affair with a beautiful girl. A child ensues, but he’s gone missing in action and, this being the 1940s, she is forced to give the baby up for adoption. But Ross eschews the tropes of romantic fiction and confounds our expectations with a novel that is far more than a simple love story.

Ranging between the mid-1930s and 2006, with a chronological structure which is not always predictable but invariably works, the novel combines romance, action and social history. Ross writes with tremendous verve and seems as comfortable in the voice of the young soldier, Philip, as she is in that of her half-Romany heroine, Rosie. Her wide-ranging story is clearly very well researched, but she uses factual information skilfully, so that the reader doesn’t really notice it but nevertheless feels as if she is in the hands of an author who knows her subject inside out. The plot twists and turns in so many directions, it keeps you in its grip to the very last page.

A hugely enjoyable read, easy yet well-informed, light yet crammed with poetic images and unafraid to confront the harshness of war and its long-lasting consequences.

Sara Bower.

“Grave comedy, tender tragedy and modern history play all in one, the scope of this fine book is anything but small. Her characters might dream of London, but her sharp-edged focus on their time and place lights up a whole era. Mixing first-hand experience with a wise unsentimental humour, not to mention some dazzling writerly tricks, Small Scale Tour is a tremendous performance.”

Philip Gross on

Small Scale Tour

Review from The Newcastle Journal: 18th December, 2013 by Peter Mortimer

Small Scale Tour, Caroline Ross (Honno Modern Fiction, £8.99)

There are many actors’ autobiographies, but good novels about the profession are thin on the ground. Even fewer are those with a setting of regional small-scale professional theatre.

Caroline Ross is married to Teddy Kiendl, one-time artistic director of Newcastle's Live Theatre Co. The couple now live in Wales and this is Ross’s second novel. Like the first, The War Before Mine, it spans two periods. Both are on Tyneside but 30 years apart, firstly when the main character, Ham, was a part of the still fairly new and impecunious Kicking Theatre Company, and later when he returns to audition for a revival of the play which was their first production.

By the second period Ham is mainly ‘resting’, stacking shelves for his eccentric Afghan corner shop employer, but still dreaming of that big break. Now, Kicking Theatre Co is in swish new premises with a clutch of marketing people and Ham’s interview with the somewhat mechanical new female director seems a universe away from the chaos, passions, insecurities, emotional disasters, confusions and blind faith he remembers. Or is Ham merely unable to adapt to a new age? Is he jealous of what Kicking Theatre has become?

The writing is humorous and perceptive and uses an imaginative device of inserting sections of invented theatre text into the narrative (Ham is now trying to make it as a writer as well). It allows the unlikely inclusion in a Tyneside novel of the Greek god of wine, Dionysus.

The book powerfully evokes that strange, irresistible, infuriating, creative, insecure and often sexually charged world in which a group of young people live hand-in-glove as they trundle their play round one night stands. It’s a world that could easily be romanticised but Ross avoids this. With two deaths at its core, Small Scale Tour can often be painful.

Possibly because, unlike her husband, the author observed this thespian behaviour from a certain distance, the book is not too incestuous. It is capable of standing back to create memorable non-theatre characters such as Afghan corner shop owner Mr Khan. It can also make telling social observations, as when the actors visit the dysfunctional mother of the young working class lad Matt who they’ve taken on as part of a government scheme. At such times, when the differences in lifestyle are laid so bare and with such powerful writing, the phrase ‘working class theatre’ can seem a bit too easy.

The public like to think of their actors in the glitzy world of chat show, celeb mag, West End and Hollywood, rather than sticking up the set in a draughty Blaydon Hall. To be fair, most actors yearn for that world also. It is only later they realise the significance and importance of that draughty Blaydon Hall.

It is to the credit of Small Scale Tour that it understands that significance and importance

too. In many ways, this fine book is an homage to

the same.

Caroline welcomes any comments or questions

so if you would like to email Caroline

Caroline Ross @jcarolineross

Poetry and Prose

Honno is an independent co-operative press run by women and committed to bringing you the best in Welsh women's writing.

A charitable organisation founded in 1909, we provide support, information and merchandise for specialists and the general public alike. We have over 3,000 members worldwide and we engage with and support diverse poetry audiences.